> Entertainment > K-pop

> Entertainment > K-pop

|

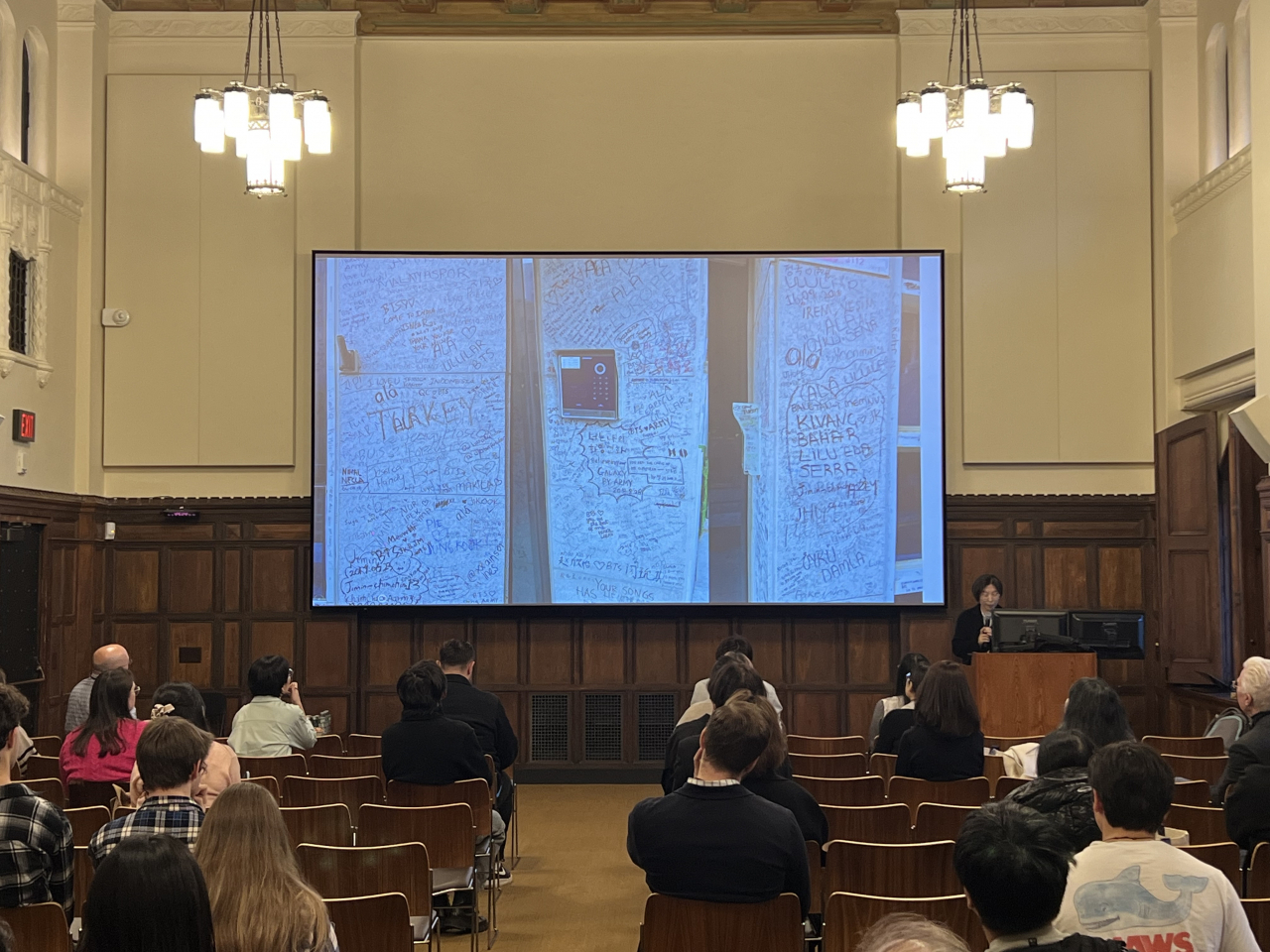

| A scholar gives a talk during the K-Pop: Musical Production and Consumption conference at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, Friday. (Kim Jae-heun/The Korea Herald) |

NEW HAVEN, Connecticut -- Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, hosted a two-day K-pop conference under the banner of “K-Pop: Musical Production and Consumption” on Thursday and Friday, featuring discussions by scholars in social sciences and the humanities alongside presentations by industry professionals. Sixteen speakers delivered talks across four sessions, examining topics ranging from fandom dynamics and musical identity to K-pop’s historical trajectory and global market strategies.

Shifting power dynamics in K-pop fandoms

Mathieu Berbiguier, a visiting assistant professor in Korean Studies at Carnegie Mellon University, explored the evolving dynamics between Korean and international K-pop fans, particularly in online spaces. His research identified a significant shift in influence, largely driven by increased economic participation from international fans.

“In 2016, when I started my research, it was not the time when international fans were able to purchase K-pop group’s albums and their merchandise, not to talk about attending their concerts. It was hard for, especially Western fans, to economically contribute as idols' new albums, merchandise items and concerts were only available in Asia,” Berbiguier said.

“But as K-pop’s popularity expanded globally with emergence of star groups like BTS, Blackpink and Twice, international fans finally got to spend money. This narrowed the economic power gap between Korean fans and international fans,” he added.

Berbiguier’s case study on Seunghan, formerly of SM Entertainment boy band Riize, highlighted this dynamic. Seunghan went on an indefinite hiatus two months after debuting in September 2023, following leaked photos and videos showing him smoking and engaging in intimate behavior with a woman. While Korean fans called for his removal from Riize, citing damage to the group’s image, international fans defended his privacy and labor rights.

“International fans' engagement in economic activities has given them voice power that was not present in 2016. Because international fans started to spend money, K-pop agencies started to pay attention to global fans' voice, which led SM Entertainment to try bringing Seunghan back in the group,” Berbiguier said.

SM Entertainment reinstated Seunghan in the group, but retracted its decision two days later due to backlash from Korean fans. The company later announced plans for Seunghan’s solo debut next year, aligning with international fan demand.

Feminist context in fan protests

Stephanie Choi, a postdoctoral researcher at the State University of New York at Buffalo, examined how Korean female fans’ protest culture reflects broader feminist movements in South Korea. She contended that while international fans often dismiss these protests as irrational or hysterical, they can be understood as expressions of feminist ideals within the K-pop industry.

“In Seunghan’s case, his act of kissing a woman is perceived as detrimental to his brand value. Protests have emerged in this context, with Korean fans criticizing the impact on his image, while international fans argue that this constitutes a violation of Seunghan’s personal labor rights,” Choi said.

International fans have criticized Korean women and girls for placing too much trust in the “pseudo-romantic relationships” marketed by idols, questioning whether they truly believed Seunghan would never date or remain “pure.” They argued that such expectations infringe on artists’ personal rights and labor conditions.

|

| An industry insider delivers a presentation during the K-Pop: Musical Production and Consumption conference at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, Thursday. (Kim Jae-heun/The Korea Herald) |

However, the issue lies in the fact that from the company’s perspective the majority of profits come from Korean fans -- mostly women and girls. For instance, 70 percent of SM Entertainment’s revenue is derived from domestic fans, with additional income from the Chinese and Japanese markets.

“Additionally, Chinese female fans have started to align with Korean female fans, creating a noticeable trend. As a result, if Korean female fans, who contribute 70 percent of the company’s revenue, and Chinese female fans, who account for a significant portion of the remaining 30 percent with Japanese, turn their backs on Seunghan, his consumer power could diminish significantly,” Choi said.

Musical evolution, cultural expression

Kim Sun-hong, a Ph.D. candidate in ethnomusicology at the University of Michigan, emphasized the importance of viewing K-pop as a musical genre rather than solely focusing on its choreography. She highlighted Suga’s 2020 single “Daechwita” as an example of how K-pop can blend traditional Korean elements with contemporary genres like hip-hop.

“'Daechwita' incorporates gugak not as a decorative tool but as a central narrative element, symbolizing authority and power,” Kim said. “This thoughtful integration amplifies the impact of his storytelling, making the song stand out not only as a musical piece but also as a meaningful cultural expression.”

Kim argued that K-pop could expand its artistic scope by exploring noncommercial projects, allowing the genre to gain recognition as an art form.

“When people think about what defines K-pop, melody often comes to mind as a key element. Compared to lyrics or rhythm, melody tends to take precedence. At its core, K-pop is about singing, and when performing, an artist’s unique traits and personality naturally shine through. K-pop doesn’t necessarily need to center around dance. Instead, it can be distinguished by how its musical genres are approached and which stylistic conventions dominate its sound,” Kim said.

J-pop’s influence on K-pop identity

Kim Sung-min, a professor of media and communication at Hokkaido University in Japan, discussed the foundational influence of J-pop on K-pop. He noted that Japan played a pivotal role in shaping K-pop’s sound and aesthetics, particularly in its early days.

“The influence of Japanese music on K-pop cannot be ignored. Japan, as a close neighbor, has played a significant role in shaping K-pop by introducing sophisticated music that resonates with Asian sensibilities,” Kim said. "This interaction has greatly contributed to the evolution of modern K-pop."

“When discussing first-generation K-pop groups like Shinhwa or H.O.T., it’s impossible to overlook the influence of Japan’s Johnny & Associates. While K-pop borrowed elements, it also developed its distinct style. For instance, H.O.T. tackled socially critical themes, and member Moon Hee-joon sported a rock star hairstyle influenced by Japan. However, while such looks were exclusive to rock stars in Japan, K-pop reimagined this by allowing idols to adopt those bold visuals, creating something entirely unique to the genre,” he added.

Kim also discussed how fans continually seek authenticity in K-pop, embracing uniquely Korean elements like sitting “Yangban Dari,” or cross-legged, or eating pizza with chopsticks, as recently observed by young fans in Mexico.

“K-pop’s openness to innovation and its pursuit of authenticity fuel its global appeal,” Kim said. “This dynamic energy sustains the genre’s popularity while allowing it to adapt to international audiences.”